Simulating Data using a Discrete-Event Approach

Robin Denz

Source:vignettes/v_sim_discrete_event.Rmd

v_sim_discrete_event.RmdIntroduction

In this small vignette, we introduce the

sim_discrete_event() function, which can be used to

generate complex longitudinal data with a continuous time scale based on

the discrete-event simulation (DES) framework (Banks et al. 2014). It is very similar to the

sim_discrete_time() function in spirit, but relies on a

completely different algorithm to generate the data. This algorithm is

usually much faster than the discrete-time approach, while also being

more precise. The drawback is some added complexity and a little less

flexibility. For example, in sim_discrete_event(),

continuous, categorical or count-based time-dependent variables are

currently not supported. Only binary variables added using the

"next_time" node type may be used.

The goal of the sim_discrete_event() function is not to

provide a general framework for DES. Multiple other R packages, such as

simmer (Ucar, Smeets, and Azcorra

2019; Degeling et al. 2025) and DES (Matloff 2017), as well as software packages

outside R have been developed for that purpose and are much more useful

in this regard. Instead, the aim of this function is to provide a

specific, but fairly general, DES model that may be used to generate

data from DAG based description of the data generation process (DGP). In

other words: if you want to perform a classic DES with interacting

agents using a classic simulation modeling approach, this is probably

not the right package for you. If you want to generate complex

time-dependent data based on a stochastic model, you have come to the

right place.

Throughout the vignette, we assume that the reader is already

familiar with the simDAG syntax. If this is not the case,

we recommend consulting the introductory vignette or the main paper

associated with this package first (Denz and

Timmesfeld 2025).

What is Discrete-Event Simulation and Why Use it?

In a discrete-event simulation (DES), the data is generated according

to a statistical model, which describes a system as a sequence of

distinct (or discrete) events that happen in continuous time and may

influence each other. Any DES starts with the generation of

individuals at

that have some characteristics, such as values of multiple covariates.

The full description of all individuals is considered to be the

state of the simulation here. This state only ever

changes when some event occurs. A simple example for an

event would be a variable changing its value from

FALSE to TRUE or vice versa. If such an event

occurs, the time of the simulation is advanced to the timing of this

event. The state of the simulation is then updated to reflect the

changes brought on by this event. Next, the time until the next event is

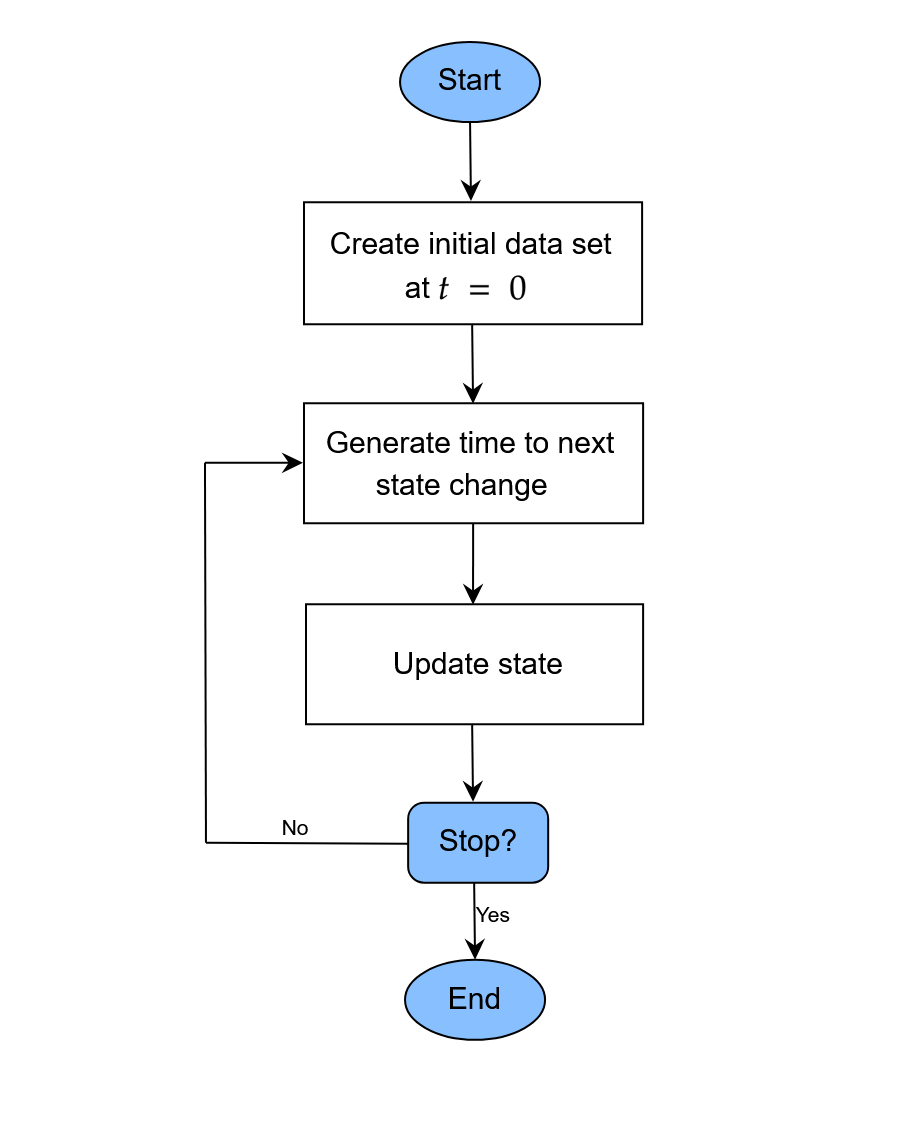

generated and the process is repeated until some condition is met. The

flowchart below gives a generalized description of a DES as considered

here.

A generalized flow-chart of the discrete-event simulation approach

This approach has many names and usages in the literature. In physics

and chemistry, the particular variant discussed here is known as the

Gillespie algorithm (Gillespie 1976,

1977), or the next reaction or first reaction

method (Anderson 2007). Formally, it is a

mathematically exact method to generate random trajectories from a known

(not necessarily Markovian) stochastic process (Masuda and Rocha 2018). Formal descriptions of

the algorithm are given in the cited literature. The most general

description of the DES (or Gillespie algorithm) implemented in

sim_discrete_event() is as follows for every

individual:

- At

,

initialize the baseline covariate values and set all

time-dependent covariates to

FALSE.

- At

,

initialize the baseline covariate values and set all

time-dependent covariates to

- For each of the considered time-dependent variables, generate the time until the next change based on some distributional assumptions (possibly dependent on any variables contained in the current state)

- Advance the simulation to the minimum of the values drawn in step (2).

- Update the value of the time-dependent variable that generated this event.

- Go back to step (2) and repeat until either some condition is met or no changes are possibly anymore (may happen if every time-dependent variable has reached a terminal state).

The sim_discrete_event() directly implements this

workflow, assuming that individuals (rows in the data) do

not influence each other. A data set at

is either simulated using the sim_from_dag() function or

supplied directly by the user (using the t0_data argument).

This data set is then updated according to the time-dependent nodes

added to the dag using node_td() calls. After

each update, the state of the simulation is saved, so that the final

output is a single dataset in the start-stop format. Below we give a

short example on how this works in practice. We use a similar example to

the one used in the discrete-time simulation vignette, to allow direct

comparisons with the discrete-time approach.

Defining the DAG

As for the other simulation functions in this package, the definition

of a DAG is the first required step. Any amount of time-independent

variables specified using standard node() function calls

are supported. Time-dependent nodes should be specified using the

node_td() function instead. Importantly, for

sim_discrete_event(), only time-dependent nodes of type

"next_time" are supported. For more examples and guidance

on how to generally define a DAG, please consult the other vignettes and

documentation pages of this package.

A single time-dependent variable

For illustrative purposes, we will start with a small comparison of

the discrete-time simulation approach and the discrete-event approach.

Consider that we are interested in simulating the time until

death for

individuals. Lets ignore the influence of any other variables for the

moment and just consider death by itself. Suppose that

death has a fixed probability of 0.01 to occur during each

time-unit.

Discrete-Time approach

In a discrete-time simulation, we would simply draw Bernoulli trials

with a probability of 0.01 at

.

If the trial returns a 1, we are done and save the time. If it returns a

0, we increase

by one and repeat until we are finished. This can be done using the

sim_discrete_time() function using the following code:

library(simDAG)

library(data.table)

set.seed(1234)

dag_dts <- empty_dag() +

node_td("death", type="time_to_event", prob_fun=0.01, event_duration=Inf)

simDTS <- sim_discrete_time(dag_dts, n_sim=10, max_t=10000000,

break_if=all(data$death_event==TRUE))

head(simDTS$data)

#> .id death_event death_time

#> <int> <lgcl> <int>

#> 1: 1 TRUE 98

#> 2: 2 TRUE 20

#> 3: 3 TRUE 13

#> 4: 4 TRUE 112

#> 5: 5 TRUE 36

#> 6: 6 TRUE 54Here, we set the max_t argument to a very large number

and told the function to stop once everyone has died using the

break_if argument. This approach works well, but it is also

incredibly inefficient in this simple example. Since death

has a constant probability of 0.01, we could also simply sample time

values from an exponential distribution with rate=0.01.

This is exactly what will be exploited in the DES approach.

Discrete-Event approach

Since we are only interested in a single variable, which has a terminal state (once you are dead, there is no going back), we only need one time-jump and thus only one iteration in the DES approach, while we needed potentially hundreds or thousands in the discrete-time approach. The following code may be used to implement this:

dag_des <- empty_dag() +

node_td("death", type="next_time", prob_fun=0.01, event_duration=Inf)

simDES <- sim_discrete_event(dag_des, n_sim=10, target_event="death",

keep_only_first=TRUE)

head(simDES)

#> Key: <.id, start>

#> .id start stop death

#> <int> <num> <num> <lgcl>

#> 1: 1 0 102.242570 TRUE

#> 2: 2 0 140.148734 TRUE

#> 3: 3 0 104.549136 TRUE

#> 4: 4 0 91.690158 TRUE

#> 5: 5 0 1.877996 TRUE

#> 6: 6 0 147.742697 TRUEThere are some differences to the output of the

sim_discrete_time() function. First, because we are using

the DES approach, the time is continuous and not discrete. Secondly, the

output is naturally in the start-stop format, because there would be no

other useful way to represent it. Because there is only one change, each

individual only has one row in the dataset and it is thus still almost

equivalent to the output of the discrete-time approach.

In this example the sim_discrete_event() output is

exactly equal to just calling rexp(10, rate=0.01), while

the sim_discrete_time() output is a discrete-time

approximation to it.

Two interrelated time-dependent variables

We will now make the example a little more complex, by including a time-dependent variable which directly influences the probability of death. Consider the following code:

prob_death <- function(data) {

0.001 * 0.8^(data$treatment)

}

dag <- empty_dag() +

node_td("treatment", type="next_time", prob_fun=0.01,

event_duration=100) +

node_td("death", type="next_time", prob_fun=prob_death,

event_duration=Inf)

sim <- sim_discrete_event(dag, n_sim=10, remove_if=death==TRUE,

target_event="death", keep_only_first=TRUE)Here, we specified two time-dependent nodes of type

"next_time". The first one denotes the

treatment, which has a fixed probability of being given to

a person. It then has an effect for 100 time units, after which the

variable turns back to FALSE. Once it is FALSE

again, it may be given to the same person again immediately, with a

probability of 0.01. The probability of the death of a

person is now no longer fixed, but a function of the

treatment status. The general probability of death is 0.001

per time unit, but it is reduced by a factor of 0.8 if the

treatment is currently in effect.

Importantly, in this simulation we had to use one of the three

arguments that define an end of the simulation: max_t,

remove_if or break_if. We specified

remove_if, so that all individuals who die are no longer

part of the simulation. Alternatively, we could have gotten a similar

effect using the break_if argument, or limit the amount of

time the simulation may run with max_t. The latter is not

very useful here, because we are interested in the time of death. If we

hadn’t used any of these arguments, the simulation would be updated

exactly 1000 times per person (default value of the

max_iter argument), because treatment does not

have a terminal state (both its event_duration and

immunity_duration are finite). The

target_event argument is only used to make the output a

little prettier.

The generated data for the first individual look like this:

head(sim, 9)

#> Key: <.id, start>

#> .id start stop treatment death

#> <int> <num> <num> <lgcl> <lgcl>

#> 1: 1 0.00000 15.65804 FALSE FALSE

#> 2: 1 15.65804 115.65804 TRUE FALSE

#> 3: 1 115.65804 168.33340 FALSE FALSE

#> 4: 1 168.33340 268.33340 TRUE FALSE

#> 5: 1 268.33340 420.23653 FALSE FALSE

#> 6: 1 420.23653 520.23653 TRUE FALSE

#> 7: 1 520.23653 606.02564 FALSE FALSE

#> 8: 1 606.02564 706.02564 TRUE FALSE

#> 9: 1 706.02564 860.85932 FALSE TRUEAs can be seen, the treatment keeps switching between

TRUE and FALSE until the death is

eventually reached. If we increased n_sim and fit a Cox

proportional hazards regression model with the time-to

death as the endpoint and the treatment as

covariate, we would be able to recover the 0.8 as the hazard ratio for

the treatment. The same strategy could of course be used for any amount

of time-varying variables.

Above, we used the prob_fun argument to specify the

probabilities, so that the connection to the

sim_discrete_time() approach is more clear. Alternatively,

we could also use the much more convenient formula

interface:

dag <- empty_dag() +

node_td("treatment", type="next_time", prob_fun=0.01,

event_duration=100) +

node_td("death", type="next_time",

formula= ~ log(0.001) + log(0.8)*treatment, link="log",

event_duration=Inf)

sim <- sim_discrete_event(dag, n_sim=10, remove_if=death==TRUE,

target_event="death", keep_only_first=TRUE)Here, we simply specified the log-binomial model as one would when

specifying a simple binomial regression model (see

?node_binomial). Note that although the results are

theoretically equivalent when the same seed is used, they are not

identical in practice, due to small floating point errors. This should

not be an issue in practice.

Some things to consider

Time-Dependent probabilities and effects

By default, the time until the next event is generated using a random

draw from an exponential distribution. This approach, however, assumes

that the probability of occurrence is independent of the time. We can

relax this assumption by using the redraw_at_t argument.

This argument allows users to specify points in time at which the time

to the next event should be re-drawn. By additionally making the

probability function supplied to a time-dependent node time-specific, we

can then use a piecewise-constant probability instead. Consider the

following code:

prob_death <- function(data) {

base_p <- fifelse(data$.time > 300, 0.005, 0.001)

base_p * 0.8^(data$treatment)

}

dag <- empty_dag() +

node_td("treatment", type="next_time", prob_fun=0.01,

event_duration=100) +

node_td("death", type="next_time", prob_fun=prob_death,

event_duration=Inf)

sim <- sim_discrete_event(dag, n_sim=10, remove_if=death==TRUE,

target_event="death", redraw_at_t=300,

keep_only_first=TRUE)

head(sim)

#> Key: <.id, start>

#> .id start stop treatment death

#> <int> <num> <num> <lgcl> <lgcl>

#> 1: 1 0.00000 32.13286 FALSE FALSE

#> 2: 1 32.13286 132.13286 TRUE FALSE

#> 3: 1 132.13286 300.00000 FALSE FALSE

#> 4: 1 300.00000 440.08265 FALSE FALSE

#> 5: 1 440.08265 540.08265 TRUE FALSE

#> 6: 1 540.08265 648.71324 FALSE FALSEIn this code, the baseline probability is 0.001 until

and then increases to 0.005. It is not sufficient to only define the

probability function this way, because then there would be no way for

the simulation itself to know that the event durations have to be

re-drawn. For example, lets say the death time drawn at

for some person is 678 and assume that treatment has no

effect for this individual. This time was generated using a rate of

0.001, so only the time until 300 is valid. At

,

we therefore have to re-draw another time from a truncated exponential

distribution with the new rate of 0.005 (truncated at 300).

The same strategy could be used to define piecewise-constant

time-dependent effects as well. One would only need to adjust the

prob_death() function so that it has a different factor for

treatment depending on the time. Using continuously

changing probabilities is also possible, but requires a different

approach. The easiest way to do this is by using the model

argument. Consider the code below:

dag <- empty_dag() +

node_td("treatment", type="next_time", prob_fun=0.01,

event_duration=100) +

node_td("death", type="next_time",

formula= ~ log(0.8)*treatment, model="cox",

surv_dist="weibull", gamma=1.5, lambda=0.0001,

event_duration=Inf)

sim <- sim_discrete_event(dag, n_sim=10, remove_if=death==TRUE,

target_event="death", keep_only_first=TRUE)

head(sim)

#> Key: <.id, start>

#> .id start stop treatment death

#> <int> <num> <num> <lgcl> <lgcl>

#> 1: 1 0.00000 40.59338 FALSE FALSE

#> 2: 1 40.59338 140.59338 TRUE FALSE

#> 3: 1 140.59338 171.25288 FALSE FALSE

#> 4: 1 171.25288 271.25288 TRUE FALSE

#> 5: 1 271.25288 314.34103 FALSE FALSE

#> 6: 1 314.34103 414.34103 TRUE FALSEHere, we use a Cox proportional hazards model with a Weibull baseline

hazard function to generate the time of death instead of

directly defining the probability functions and drawing values using an

exponential distribution. Since the Weibull distribution is not constant

over time, this is a valid strategy if we want continuously changing

baseline event probabilities.

In theory, the same strategy could be used for any other

time-to-event model, such as Aalen additive hazards models, accelerated

failure time models etc. Users only need a function that simulates data

from such models and directly allows left-truncation. Currently, only

Cox and Aalen models are supported through the model

argument, but we are working on further built-in options.

Categorical / Count / Continuous variables

With the current implementation, only time-dependent variables are

supported. There is no way to easily integrate time-dependent

categorical, count or continuous variables instead. If these are

required, users may need to use the sim_discrete_time()

function.

Discussion

The sim_discrete_event() function has multiple

advantages over its sibling, the sim_discrete_time()

function. As a general rule, if a DGP can be described in terms of only

binary time-dependent variables (plus an arbitrary amount of

time-constant variable) it should be possibly to use both functions. In

this case, the sim_discrete_event() approach is often much

faster and more efficient and thus preferable. If more complex data is

required, the discrete-time simulation approach offers more flexibility,

while also being easier to understand, at the cost of computational

time.